Kid Charlemagne and Bear

Steely Dan is known for many things, such as fusing rock and jazz, making guitarists do more takes than anyone other than Phil Spector and being named after a fictional sentient dildo, but perhaps chief among them is their penchant for wry, dark, literary lyrics. I think the best example of this trademark Steely Dan lyrical style is the historical bio-song Kid Charlemagne, the lead single from their 5th LP The Royal Scam, which tells the story of the downfall of self-proclaimed “King of Acid” and Grateful Dead financial backer/soundman Owsley “Bear” Stanley with a Thomas Pynchon-esque level of psychedelic noir atmosphere.

Walter Becker and Donald Fagen had been building up to this sort of story-song masterpiece and these kinds of ominous vibrations over the course of the albums that preceded The Royal Scam. One need only look to jams like “Barrytown” from Pretzel Logic, which details Fagen’s annoyance over a run in with a moonie, or “My Old School” from Countdown to Ecstasy, a song about how pissed off he was to get caught up in a minor drug bust at his alma mater Bard College, to see the knack for exploding the details of a fleeting dramatic situation out into a shadowy maze of sly cultural references and mysterious signifiers. Songs like “Any Major Dude Will Tell You” and “Doctor Wu” (You should check out Minutemen’s cover) show his recurring interest in drug culture and the charismatic, ambiguous characters that inhabit that world. Arguably, there is no greater drug figure-head in the history of the American counter-culture than Owsley Stanley. In him, Steely Dan had found the perfect muse for the ultimate expression of their lyrical style.

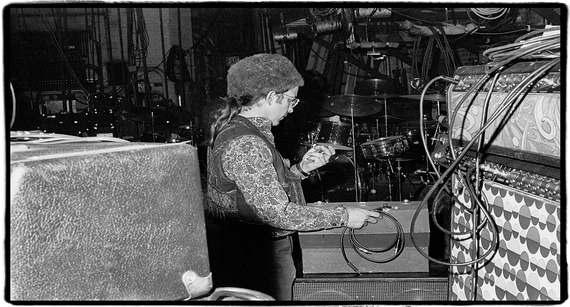

Kid Charlemagne is an apt nom de guerre for Bear. The real Charlemagne united most of Western Europe in the middle ages, laying the groundwork for Europe as we know it today. Owsley Stanley, a skilled self-taught electronics engineer, chemist, and former professional ballet dancer, united the hip youth of America in tripping balls and consciousness expansion with tabs and blotters of his trademark acid in the heady years prior to the scheduling of LSD as an illegal drug. The Merry Pranksters, the “Acid Tests”, the bay area and LA psych scenes, and that one episode of Dragnet were all fueled by Owsley’s doses. By his own calculations, he distributed as many as ten million hits between 1965 and 1967. This of course, could not last, and Stanley’s lab in Orinda, California, in the hills east of Berkeley, was eventually raided. He continued to work for The Grateful Dead until their infamous New Orleans bust (immortalized in another psychedelic noir story song, “Truckin’”), accumulating along the way an epic stash of live recordings of the San Francisco music scene of the late 60’s, including tapes of Johnny Cash, Miles Davis, Jimi Hendrix, and Blue Cheer (who might be named after one of his concoctions), among many others. After the New Orleans bust he served two years in prison and went underground upon his release, later becoming an Australian citizen.

Just as in songs like “Barrytown”, Becker and Fagen’s spite and derision seems to be firing on all cylinders when handling the subject of Owsley Stanley. “Kid Charlemagne” mocks his heyday, reducing the impact of the Merry Pranksters to an eye-catching “technicolor motorhome”, and revels in his failure, with condescending lines like “son you were mistaken, you are obsolete, look at all the white men on the street”. The aesthetic of Steely Dan could not be more opposed to the aesthetic of the Haight-Ashbury true hippy moment, and at first glance this song seems to be a straight-up critique of that cultural movement and an exposition of its paranoid flash-in-the pan guru. What could be more different than the free form jamming of the Grateful Dead, recorded live, with tons of flubs, awkward stage banter, and crowd noise; and the super slick, dialed-in studio soul-jazz bounce of a Steely Dan hit? What could be more opposite than a thousand dirty teenagers writhing to noise in a warehouse covered in day-glo paint and acid spiked orange juice and the lone audiophile dropping the needle of his Bang & Olufsen turntable on a hot stamper pressing of Aja in his custom designed record den, swirling a neat scotch in a crystal rocks glass? What makes ”Kid Charlemagne” so great is that it cannot be that simple. Philosophers from ancient Greeks to Buddhists to post-modernists have observed a phenomenon known as the unity of opposites, and this song expresses it perfectly.

The similarities between Steely Dan and their scruffy protagonist are obvious from the beginning. “Just by chance you crossed the diamond with the pearl” describes Owsley’s nailing down an acid formula rivaling that of pharmaceutical company Sandoz, but it also describes the singular musical fusion of Steely Dan, which at its very best has never been replicated. I’ve never described a band and said “this sounds like Steely Dan”, because that’s never really been true. I think Steely Dan can lay claim to having accomplished, with an album like Aja, the peak of their expression, an alchemical fusion of disparate influences, equipment and personnel with their personal vision and sharply honed skills to create a new and mind-bending experience. I’m sure an aging hippy that had the pleasure of sampling some of Bear’s wares would make a similar observation. The song goes on describe Bear’s dedication to his craft: “On the hill the stuff was laced with kerosene, but yours was kitchen clean”; Walter Becker and Donald Fagen’s unyielding perfectionism and will to make music that still stands as some version of maximizing the potential of an analog recording studio is a result of the same will that drove Owsley to be a ballet dancer, electronic and sound engineer, and the best underground LSD chemist known to history. Both efforts left lasting marks in their respective fields.

From this point, the lyrics begin to describe Stanley’s downfall, which for me can only suggest another interesting unity between these ostensible opposites. Stanley himself fell from grace, but acid, the thing he made ubiquitous in the American counter-culture, is as popular as ever, even going square, being used in “micro-doses” by Silicon Valley business men to give them a creative edge. The godheads of the musical culture he helped to create, The Grateful Dead, have also undergone a somewhat unexpected re-birth, playing to tens of thousands once again, with John Mayer on lead guitar for some reason (I guess because he can shred and handle his doses?). While not as precipitous, Steely Dan has had a decline as well (who’s jamming Everything Must Go on a regular basis?) but their music, in a way that is divorced from them, in that it can be heard again without any knowledge of their involvement as artists, is as relevant as ever in the form of breaks and samples for hip-hop hits, memorably "Eye Know" by De La Soul, “Déjà vu (Uptown Baby)” by Lord Tariq and Peter Gunz, and “Champion”, by Kanye West, which samples the chorus of “Kid Charlemagne” (these are the obvious ones but the list goes on). Fagen and Becker were apparently not impressed with the way West used “Kid Charlemagne” and wanted to block the sampling rights, but West wrote them an actual letter saying how much the song meant to him. Did Kanye know about Owsley, and feel a kinship with the King of Acid, or did he identify with the song on an entirely different level unique to him? That is the power and mystery of Steely Dan at their height.

The second half of the song tells, through the character of Owsley, a story that’s familiar by now from cultural milestones such as Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas and Inherent Vice…the comedown from the hippy high, the buy-in to square society by the majority of the former freaks, and the consequences for those that won’t let go of their outlaw status. There is a lyrical twist at the end of the song that fully embodies the unity of opposites; the perspective shifts from a third person, judgmental “you” to a more inclusive first person, “we”…for the last verse, Fagen and Stanley are full-on partners in crime. “Clean this mess else we’ll both end up in jail, those test tubes and the scale, just get it all out of here”…the imagery is concrete, the paranoia is visceral. The penultimate lines truly give this song a climax, in large part due to Fagen’s amazing performance of this miniature conversation between, for all intents and purposes, him and Stanley: “Is there gas in the car? Yes, there’s gas in the car, I think the people down the hall know who you are”. I hope by this point in this article you have listened to the song because text does not do this part justice. Finally, Fagen steps back: “cause the man is wise, you are still an outlaw in his eyes”. He’s resumed that judgmental third person stance, but we know that he was asking if there was gas in the car, sharing with Owsley Stanley the existential dread caused by staring into the setting sun of his cultural relevancy. At the peak of his considerable, dark, moody, lyrical powers, Donald Fagen was able to invoke the character of Owsley Stanley, King of Acid, to express the fundamental truth of the unity of opposites.

I would be remiss if I did not discuss the musical aspects of “Kid Charlemagne” just a bit, because beyond the lyrical fireworks it truly is a jam. It’s anchored rhythmically by a disco/soul/funk backbeat created by Steely Dan stalwart session bassist Chuck Rainey and legendary drummer Bernard Purdie, who has played with everyone from Albert Ayler to Cat Stevens, which I think means everyone, and whose nickname is Mississippi Bigfoot. The funk vibes are turned up by the presence of session man Paul Griffin, who played keys on Highway 61 Revisited, rocking a choppy clavinet. This is really a stripped down funk-rocker for a Steely Dan song, filled out by jazz pianist Don Grolnick on Fender Rhodes E-piano, Walter Becker on rhythm guitar, and jazz and session guitarist Larry Carlton playing an insane guitar solo that Rolling Stone ranked the third best on record. That guitar solo, the musical centerpiece of the song (along with Donald Fagen crooning “there’s gas in tha caaaaaaah”) is another moment where the unity of opposites is invoked: the solo is strange, modal, distorted, psychedelic and jazz inflected (not unlike a Jerry Garcia solo), contrasting sharply but tastefully with the razor sharp rhythms and melodies of the song and summoning the lysergic counter-culture vibes of the song’s anti-hero.